New to Fitness Program Design: A Real Client Example From OPEX Coaches

A “new to fitness” client isn’t always new. Sometimes they’re returning after years away, carrying fear, old injuries, or a bad past experience. In this episode of Behind The Design, OPEX coaches Brandon Gallagher and Daniel Persson walk through what that actually looks like in program design, using a real in-person client as the example.

The lesson is simple: early training isn’t about fancy workouts, it’s about building trust, keeping things safe, and stacking small wins until the client starts to believe again. That’s how a person goes from “not sure I can do this” to deadlifting, lunging, and enjoying training.

Why “everyday clients” can make coaching harder (and more rewarding)

A lot of coaches want the high-level athlete. It sounds more exciting, and the training can look more complex on paper. Brandon and Daniel both point out that lifestyle clients often bring a different kind of challenge, and it can sharpen coaching skills fast.

Competitive athletes usually show up ready to train. They tend to recover better, they often protect their sleep, and their schedule makes training a priority. They also have a bigger “buffer” for mistakes. If programming isn’t perfect, they can still adapt and perform.

A lifestyle client can’t absorb that same margin of error. The wrong early session can wipe them out for days. Too much soreness can stop momentum. A program that looks “impressive” can feel scary or discouraging. With this group, coaches have to think beyond sets and reps. They have to account for time limits, stress, confidence, and what the client believes is safe.

Daniel also frames the reward differently. Helping a lifestyle client build consistent movement, improve health markers, and gain years of better living can feel bigger than medals. Getting someone from not training to training is a huge shift, and it starts with good decisions early.

The first “assessment” is often a conversation, not a workout

Brandon’s client example is a 69-year-old man (nearly 70) who had a heart attack and an aortic valve replacement about three years earlier. After that, he spent years barely moving, and he came into the gym nervous and unsure he could trust the process.

Before talking exercises, Brandon focused on what the client experienced and what had stopped him from sticking with training in the past. One moment stood out: a treadmill speed of 2.5 triggered fear because it matched the speed where he first felt chest tightness before the heart attack. That one detail created a mental barrier around cardio and higher heart rates.

That’s the part many programs miss. For a returning client, “fitness” can feel like walking back into the scene of the crime. Until the coach addresses that fear, training plans don’t matter much.

Daniel shares a similar story from his coaching, working with a client who had a heart attack and didn’t feel safe at higher heart rates. The principle stayed the same (conditioning work), but the execution changed. The client completed the session with a heart rate cap, using what felt safe while still training.

The big idea: principles don’t change, but the plan has to match the person.

Week 1 program design: simple movements, repeatable wins

Early on, Brandon’s priority wasn’t a “perfect” training split. It was getting the client through a full session, building confidence, and keeping the learning curve low.

The client trained two days per week in person. Outside those sessions, the main goal was walking more.

Day 1: a full-body triset without high skill

The first training block used a triset:

Air squats to a box

Lat pull-downs

Dumbbell hammer curls

The order was intentional. The hardest skill piece came first (the squat pattern). Then the program moved to a machine-based pull, then a simple arm movement. That shift helped reduce overall fatigue and made it easier to keep moving.

This is also where Brandon calls out a common coaching mistake: trying to do too much too early to “prove” value. For brand new or returning clients, a simpler session often works better. They can feel the work without getting overwhelmed by technical demands.

Daniel adds an important note: because this was an in-person client, Brandon could safely run a longer triset and watch the client’s response in real time. If it were remote coaching, Daniel would likely break it up more to avoid pushing heart rate too high without supervision.

Day 1 continued: controlled pressing and hinge practice

The second block included:

Barbell rack push-ups (adjustable height)

RDL pattern work (starting with a box as a target)

Band pull-aparts

The push-up setup gave the client a way to press through a full range of motion without having to do floor push-ups. The RDL work wasn’t about load yet, it was about learning the hinge and feeling hamstrings and glutes. The takeaway stays consistent: early sessions should create the base, not test limits.

Recovery and walking: building fitness between sessions

With a new or returning client, the recovery day matters as much as the training day. Brandon’s weekly rhythm was training, rest, training, rest. Even simple sessions can cause soreness when someone hasn’t trained in a long time.

Outside the gym, the focus was walking. The client started low, around 1,000 to 2,000 steps per day, and Brandon aimed to build toward 5,000 steps as a realistic first target. That smaller goal mattered because jumping straight to 10,000 can set people up to fail, and failure kills momentum.

Daniel highlights a mindset problem many beginners have: they think training only “counts” if it’s three to five sessions per week. But if the baseline is nothing, even one session plus more walking can drive real change. Early progress comes from doing something consistently, not from copying an advanced routine.

Month 2 progression: add patterns, keep familiarity

As the client gained confidence, Brandon progressed the plan without turning it into a brand new program every week. The strategy was to keep what the client recognized, then add one or two new movements.

One key change was moving from squat-to-box work to a supported split squat (assisted at the rack). That introduced a single-leg pattern while staying stable and controlled.

At the same time, familiar exercises stayed in place. Brandon calls this a “sneaky” win: when clients see something they already know, anxiety drops. They walk into the session thinking, “I’ve done this before.” That matters more than people think.

Brandon also distinguishes progressions from random change. A hinge pattern moving from “RDL with box guidance” to “dumbbell deadlift” is a progression. The goal stays the same, the complexity rises a little, and the client keeps stacking skill.

Daniel adds another coaching angle: using exercise variation as a teaching tool. When clients learn to see movements as patterns (push, pull, hinge, squat, lunge), they stop thinking every exercise has a completely different rulebook. That reduces overwhelm and makes training feel learnable.

Seven months later: what “return to fitness” can look like in January

By January, the client’s program looked like a “real workout,” but the foundation was still the same. Consistency did the heavy lifting.

Highlights from the current week:

Warm-up squats (sometimes with counterbalance)

Deadlift at 150 pounds for sets of six (Brandon notes three sets that week)

Safety squat bar-style machine work to squat without shoulder limits

Single-arm dumbbell overhead press paired with a three-point dumbbell row

A full 30-second plank from the floor (first time in about five-plus years)

Barbell rack push-ups (kept in because the client enjoys them)

Chest press machine at 70 pounds

Lat pull-downs at 70 pounds

Unassisted weighted reverse lunges, a major independence win

Sled pushes for conditioning and lower-body drive

The results weren’t just gym numbers. The client was down nearly 20 pounds, and Brandon reports that key health markers and blood work were moving in the right direction. Even better, the client started getting comments from others that he looked and moved differently.

There’s also a human detail that sticks: when people tell him he looks different, he jokes that it’s just a haircut.

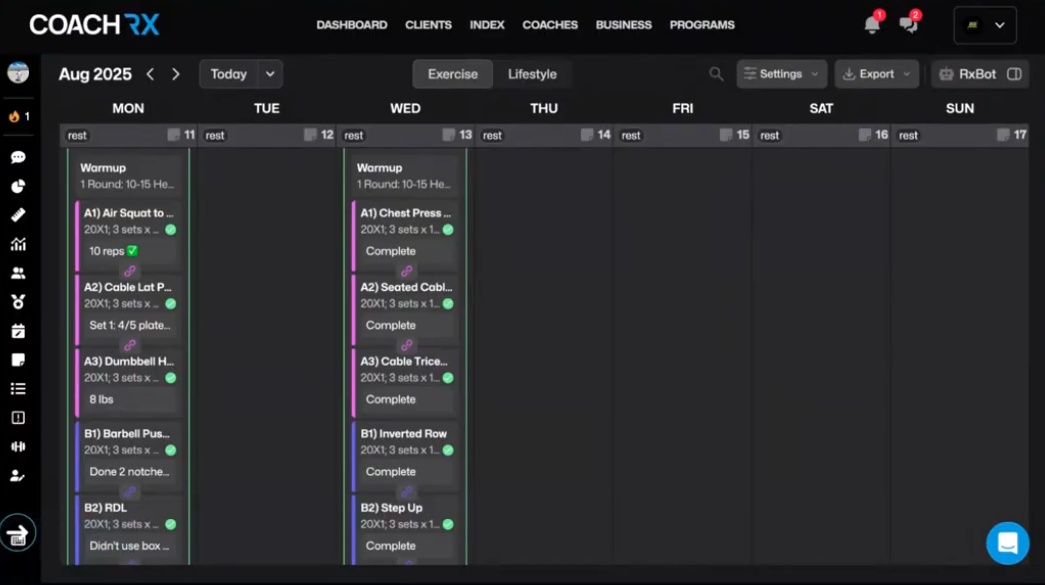

Using CoachRx and lifestyle tools without losing the relationship

The episode also touches on tools and systems, including CoachRx. Daniel mentions using the lifestyle calendar heavily, sometimes even as the only plan for certain clients. It can guide daily movement, habits, and nutrition behaviors without forcing everything into a traditional “workout session” box.

Brandon’s in-person client didn’t use much tech, so Brandon handled the app side and relied more on texting and in-person check-ins. Both coaches make the same point: tools should support the coach-client relationship, not replace it. If tech creates distance or overwhelm, it’s not helping.

For those exploring the platform mentioned in the episode, OPEX offers a CoachRx free trial and information on the OPEX Method Mentorship program. Brandon and Daniel also share coaching content on Instagram at Brandon Gallagher’s BG Perform account and Daniel Persson’s Instagram.

Conclusion

This client story makes one point hard to ignore: a strong “return to fitness” plan starts with less than most coaches think, then builds week by week. The early wins are often psychological, learning that the body is safe and capable again. When the program stays simple, repeatable, and personal, the weights go up, the fear goes down, and the client starts to own the process. What would change in coaching if the goal shifted from impressing clients to helping them trust their bodies again?

Connect with the coaches

Brandon Gallagher: Brandon’s Instagram (@bgperform_)

Daniel Persson: Daniel’s Instagram (@danielcapersson)

Join us live on Tuesdays mornings 10:30am EST on the OPEX YouTube Channel

Start your free 14-day CoachRx trial and bring principled programming, habit tracking, and high-touch communication all in one seamless coaching command center.