MMA Athlete Peaking Program Design (Part 2): Week Structure, Lifts, and Conditioning

Peaking an MMA athlete isn’t about doing more work, it’s about putting the right work in the right place so the fighter can show up sharp, healthy, and ready. In this episode of Behind the Design from OPEX Fitness, coaches Brandon Gallagher and Daniel Persson move from concepts into real program design, using a fight camp template built for a gym with amateur fighters.

If you’ve ever wondered how to balance sparring stress, strength work, plyometrics, and conditioning without burying the athlete, this breakdown gives a clear look at how the pieces can fit.

The big picture: how Brandon approaches MMA peaking

Brandon’s starting point is simple: most of the time, a fight peak sits around 4 to 6 weeks. That window is long enough to build the key outputs without rushing the athlete into fatigue, and short enough that the plan stays focused on what matters for the fight.

A major theme is stacking stress intelligently. Sparring is already a high output, high risk, high nervous system cost day. So instead of scattering hard work randomly, Brandon prefers the classic approach of high days high, low days low. If Monday is a hard spar, that same day can also carry a heavy lift, because the “hard” stress is already there. Then the next day can be kept more technical and lower intensity to support recovery.

This matters because MMA isn’t one sport. A weekly schedule may include wrestling, jiu-jitsu, Muay Thai, boxing, plus MMA-specific sessions, all with different demands. A program that ignores that reality will either under-train key qualities or pile stress until the athlete breaks down.

The example program Brandon shares was built for a gym in Ireland (FAI) with younger fighters who generally had a lower training age. That drives exercise choice and complexity. The goal isn’t to show off fancy tools, it’s to get reliable training effects with low confusion and lower risk.

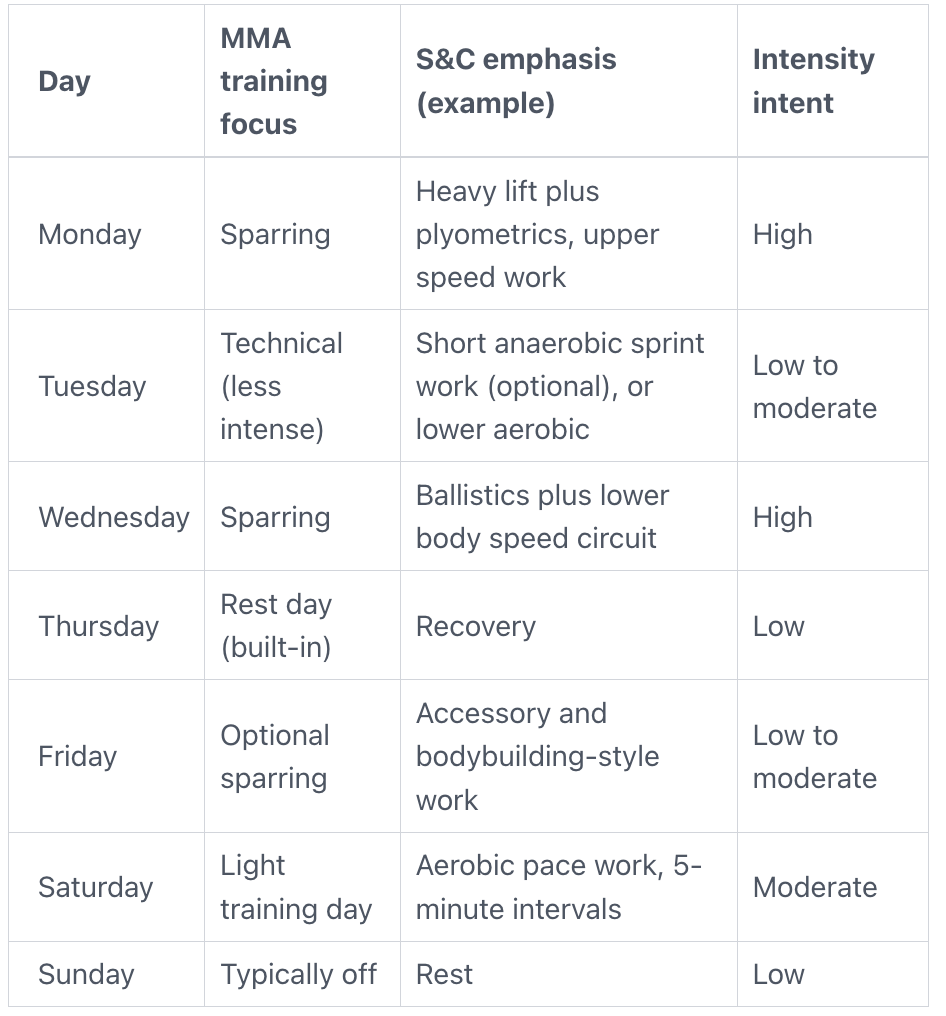

A sample weekly structure built around sparring days

At FAI, the sparring schedule Brandon planned around was Monday and Wednesday as guaranteed sparring, with Friday as optional. That’s a lot of contact work, which makes weekly organization even more important.

Here’s the “shape” of the week he described, with strength and conditioning placed around technical and sparring demands:

Two details stand out:

First, Brandon often prefers placing harder lower body work later in the week, because heavy legs early can disrupt the rest of the week’s MMA training. If a fighter crushes their legs on Monday, the soreness and fatigue can spill into Tuesday and Wednesday.

Second, the plan is built to be adjustable. It’s a gym-level template, not a single athlete’s perfect plan. Brandon is clear that individual needs, limitations, and fight schedule would change the details.

Building the session: warm-up, plyometrics, then speed strength

On sparring days, Brandon still wants athletes to touch strength and power, but with lower volume and higher intent. A typical session structure starts with a consistent warm-up flow:

Heel-to-toe work, single-leg patterns, low-level plyometrics, then higher intensity plyos and ballistics. The warm-up isn’t filler. It sets positions, prepares tissue, and builds repeatable movement quality that carries into harder work.

Plyometrics that progress without guessing

One plyo series Brandon highlights is a depth drop progression:

Depth drop and stick (landing mechanics)

Depth drop into a jump (absorb force, then produce force)

Depth drop into a redirect (absorb, produce, then change direction)

The point is not just jumping. It’s teaching the body to handle force and then use it. Brandon also describes a broader way to cycle plyometrics over time, based on the athlete’s experience:

Force absorption first, then non-countermovement jumps, then countermovement jumps, then more advanced change of direction work closer to competition.

It’s also a year-round tool. You can scale the box height up or down and still train the same pattern.

Why trap bar speed work shows up often

After plyos, Brandon likes an explosive movement such as a banded trap bar deadlift. The band creates accommodating resistance, lighter at the bottom and heavier near lockout, so the athlete can move fast while still feeling rising tension.

He and Daniel discuss why trap bar work often wins for fighters, especially those with a lower training age:

The trap bar tends to put athletes in a more natural pulling position, reduces the complexity of bar path management, and often reduces low back stress compared to straight bar deadlifts. For speed-focused work, that matters. If the athlete fights for position, they can’t fully commit to intent.

Daniel brings up a useful filter for exercise selection: complexity can’t get in the way of the goal. If the goal is explosive hip extension, you might not need Olympic lifting. A simpler tool can get the effect without turning the session into a technique clinic.

Speed circuits and French contrast, without burning the athlete

Brandon uses “speed circuits” to create high intent work in short doses. A key example is an upper body circuit built like a French contrast pairing, using an overcoming isometric to prime the nervous system before an explosive throw.

One circuit he shares includes:

Bench press into pins (overcoming isometric), then a wall ball chest pass, then banded repeated pulls.

He explains the difference between isometric types:

An overcoming isometric means pressing or pulling against an immovable object, trying to move it. A yielding isometric is holding a position against load. Brandon prefers overcoming isometrics here because they create high force intent, which can carry into the next explosive rep.

The sets are short, reps are low, rest is built in, and output matters. The goal is not to crawl out of the gym exhausted. The goal is repeatable, high-quality rounds with some fatigue, plus enough recovery to come back and do it again.

This is also where Brandon references “micro-dosing,” using the rest windows efficiently and understanding that even within short rounds, performance will drop off. The plan is designed so the athlete can still express force after each rest period, not just survive.

Core training that matches MMA: tension, breathing, and control

Brandon keeps core work simple and repeatable. His favorites for MMA are:

Ab wheel rollouts

Hanging knee raises (often with elbow supports, if available)

The reason isn’t that other movements are useless. It’s that these cover a lot of what fighters need without adding fluff.

Ab wheel rollouts train resisting flexion and extension while keeping a strong trunk position. Hanging knee raises train flexion and extension while the athlete must stabilize the upper body and control the pelvis.

A major point Brandon makes is that MMA conditioning problems aren’t always “cardio” problems. Fighters often struggle because they can’t breathe under pressure. When someone is pinning your torso and your body is tense, breathing changes. Then the athlete has to release, move, and re-engage without panicking or dumping energy.

Daniel adds a practical performance lens: athletes need to coordinate how much tension they use. If you brace at one rep max intensity all the time, you can’t breathe, and you can’t keep moving. The skill is matching tension to the task, then releasing it when you need speed and movement.

Conditioning choices: short sprints and 5-minute nonstop efforts

Brandon shares two conditioning approaches used in the template: short anaerobic intervals, and longer “keep moving” rounds that map to the feel of an MMA round.

Anaerobic sprint pairing: bike and SkiErg

One example is:

10-second bike sprint, 15 seconds rest, 10-second SkiErg sprint, then longer rest (2 minutes), repeated for multiple rounds.

Brandon’s goal isn’t to crush the athlete. Fighters already get a lot of anaerobic stress in training. This is a controlled dose that can be progressed over weeks, often by time first (10/10 for a couple weeks), then 12/12, then pushing toward 15 seconds while adjusting rounds as needed.

He also explains why splitting the sprint across two tools can help: the athlete avoids the big performance crash that often happens if you demand 20 seconds of all-out output on one machine. The brief reset and switch keeps effort high, but more consistent.

The 5-minute “you can’t stop moving” aerobic piece

For Saturday aerobic work, Brandon likes a format that forces nonstop movement, such as:

5 minutes on an Assault Bike at a sustained pace, rest 2 minutes, repeat for multiple rounds.

He’s blunt about why this matters: in MMA, you can’t stop moving. If you stop, you’re a target. Training that reality means practicing sustained output for the full length of a round, then managing short rest.

He also prefers cyclical tools like the Assault Bike because they’re easy to track and hard to hide from. You can measure RPM, calories, watts, distance, and see instantly whether the athlete is holding a steady pace or coasting.

Daniel adds another reason mixed-modal conditioning often goes wrong: many movements have a “fixed cost.” A pull-up costs what it costs, you can’t dial it down like bike wattage. Add too much skill or too much fixed-cost work, and athletes end up standing around. If the purpose is five minutes of movement, the design has to remove excuses.

Ballistics, lower body speed work, and the Friday accessory day

On Wednesday’s sparring day, Brandon’s template uses med ball throws to train upper body power with low joint stress:

Kneeling rotational tosses, punch throws, and side slams.

They also note a real-world annoyance: upper body throws are effective, but the reset takes time. You throw the ball, chase it, set again, and that changes how you dose volume. It’s still one of the clearest ways to express intent for upper body power.

Lower body speed circuit with isometrics and overspeed jumps

A lower body speed circuit Brandon shares includes:

Deadlift into pins (overcoming isometric), an iso squat hold (yielding style), then a band-assisted squat jump (overspeed).

He explains overspeed jumping simply: the band helps remove some bodyweight so the athlete moves faster than normal, which challenges the nervous system in a different way than loaded jumps.

Friday, when sparring may be optional, becomes a lower stress accessory day. The intent is to build tissue tolerance and “armor” without adding more nervous system fatigue. Plyos are kept basic, lifting stays moderate, and the athlete leaves feeling better than when they walked in.

Micro-dosing: splitting sessions around sparring for better recovery

One of the most practical takeaways is how Brandon organizes the day when sparring is the anchor.

A simple version looks like this:

Do the warm-up and plyometrics before sparring, spar, then take a short break (hydrate, quick snack, change clothes), and lift soon after while the body is still warm.

Brandon used this approach with a fighter he coached closely (Ian): warm-up plus plyos, spar, then a short lift, all inside a tight 2 to 2.5-hour window. The payoff is the rest of the day becomes real recovery time, not a long dragged-out training day that eats up energy.

This is also how the high and low week rhythm stays clean. Hard days stay hard, easy days stay easy, and the athlete has more space to adapt.

Conclusion: simple choices, placed well, add up in a fight camp

A strong MMA peaking plan isn’t built on secret exercises. It’s built on smart placement of stress, repeatable outputs, and keeping volume under control while intensity stays meaningful. Brandon and Daniel’s breakdown shows how high days high, low days low, simple power progressions, and trackable conditioning can fit around the reality of MMA training.

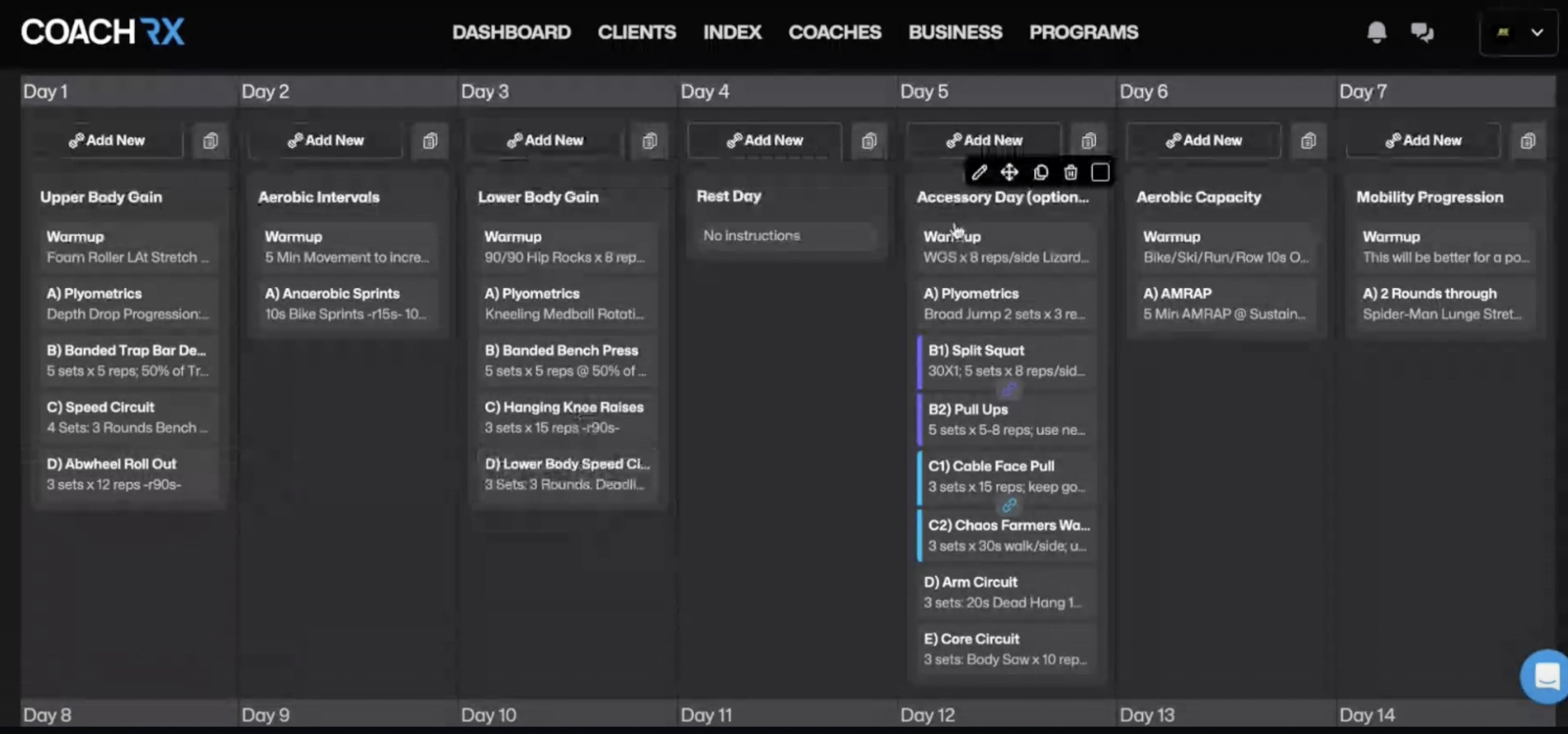

If you want to follow more of their work, connect with Brandon Gallagher at Brandon Gallagher on Instagram and Daniel Persson at Daniel Persson on Instagram. For coaches who want to see how programs are delivered and tracked, OPEX also shared a CoachRx free trial and details on OPEX Method Mentorship.

The best question to leave with is simple: does your plan help the fighter recover, repeat high output, and keep improving, or does it just make them tired? That answer usually tells you whether the peak is heading in the right direction.

Connect with the coaches

Brandon Gallagher: Brandon’s Instagram (@bgperform_)

Daniel Persson: Daniel’s Instagram (@danielcapersson)

Join us live on Tuesdays mornings 10:30am EST on the OPEX YouTube Channel

Start your free 14-day CoachRx trial and bring principled programming, habit tracking, and high-touch communication all in one seamless coaching command center.